This blog assignment asks you to read Wendell Berry's essay "What Are People For?" and a selection from Bill Thomas's What Are Old People For, and then identify three points of agreement and three points of disagreement in the two pieces.

In this blog, I want to focus not on the content of what you will write, but on the way you should go about writing this. First, make sure that you have done the reading carefully and understand their overarching arguments as well as the details they use to support those arguments.

Then, identify the points of agreement and disagreement and make sure they are accurate. Look for claims with some substance, not just vague or very broad points. Throughout, focus on the ethical dimensions of these writings. Neither author is an ethicist but both pieces are very relevant to the big questions we ask in social ethics: what is a good society? what obligations do we have to others? What makes a human life good, valuable, and worthwhile? And so forth. Feel free to go back to Weston for some reminders about these points.

Social Ethics@UF

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

Thursday, October 17, 2013

Outdoor cats, birds, and values

The question for this week asks you to identify the values at stake in both sides of the feral cat controversy and then to explain how this is an ethical dilemma.

While this dilemma is hardly black-and-white, it is possible to identify two pretty clear-cut sides. The first includes environmental advocates, ecological scientists, and bird lovers who believe that outdoor cats kill many native wild birds and thus cause a great deal of harm to ecosystems. This group values ecological integrity, native wildlife, and the overall good of the environment.

On the other side are people who value individual cats. They do not think that primary moral good lies in a collective, such as an ecosystem or even a species. Instead, the main good for this group is individual life.

The interesting thing about this debate, or controversy, is that people on both sides consider themselves animal lovers and nature lovers. Their different positions on outdoor cats come in art from their different beliefs about the damage that cats do to bird populations and the effectiveness of lethal and non-lethal management strategies for outdoor cats. Thus the conflict between values is also a conflict about information or data.

The same is true for many issues in social ethics. Often people share some core values -- they value democracy, or freedom of religion, or children, for example -- but they disagree about the best way to support and protect what they value.

While this dilemma is hardly black-and-white, it is possible to identify two pretty clear-cut sides. The first includes environmental advocates, ecological scientists, and bird lovers who believe that outdoor cats kill many native wild birds and thus cause a great deal of harm to ecosystems. This group values ecological integrity, native wildlife, and the overall good of the environment.

On the other side are people who value individual cats. They do not think that primary moral good lies in a collective, such as an ecosystem or even a species. Instead, the main good for this group is individual life.

The interesting thing about this debate, or controversy, is that people on both sides consider themselves animal lovers and nature lovers. Their different positions on outdoor cats come in art from their different beliefs about the damage that cats do to bird populations and the effectiveness of lethal and non-lethal management strategies for outdoor cats. Thus the conflict between values is also a conflict about information or data.

The same is true for many issues in social ethics. Often people share some core values -- they value democracy, or freedom of religion, or children, for example -- but they disagree about the best way to support and protect what they value.

Tuesday, October 1, 2013

Mothering.

For Sara Ruddick, “mothering” means something very different from the familiar definitions. To understand the ways that mothering might contribute to social and political ethics, it’s necessary first to clarify what mothering in fact means to her.

First, mothering is not confined to women. As a feminist, Ruddick does not believe that nurturing and caring are naturally – or should be – limited to women. Mothering as she describes it is a powerful and positive practice that men and women alike should undertake. In contrast to “fathers,” who are hierarchical, authoritarian, and sometimes violent in their exercise of power, “mothers” seek to help the people they care for be safe and thrive.

Last, mothering is as much a political practice as much as it is a personal one. Like all care ethicists, Ruddick defines care and nurture in social and political terms. This means that care entails not only direct personal interactions with vulnerable and needy humans but also work to create the conditions that those people need in order to thrive. This may require explicitly political actions, such as changing laws, protesting wars, or redistributing public funds.

For Ruddick, "mothering" provides a strong foundation for social and political ethics in a couple of ways. First, mothering clarifies primary political and moral goals: a society in which children can be safe, healthy, well-cared for, and adequately prepared for adulthood. Second, mothering provides the means for achieving these goals: in and through relationships of care and reciprocity. It suggests a way to build a good society through personal as well as political means, and further, that these different approaches are ultimately united.

Monday, September 23, 2013

Personal Virtue and Social Conditions

The blog assignment for this week asks us to think of a morally admirable person and describe the ways his or her virtues are connected to the society in which s/he lives or lived. The second half of this assignment is especially important, since there is sometimes a tendency to think that virtuous people exist in a sort of cultural and historical vacuum. In fact, every virtuous person is virtuous because of and in the context of his or her particular experiences -- personal as well as social.

Some people overcome great personal and social obstacles to practice virtue and to help make their society better. Good examples of such people are members of minority groups, women, and others who suffer social exclusion and/or repression. Despite lacking access to the same resources as more powerful members of society and experience injustice and often physical and emotional abuse, they do not take the path of anger, bitterness, or virtue but rather astound both their enemies and their allies with their example of virtues such as patience, forgiveness, and generosity. Martin Luther King Jr. is an outstanding example of this kind of virtue.

Other virtuous people seem to become good not in spite of but because of their social conditions. Their personal histories, families, economic advantages, and cultural training all equip them to embody certain virtues. Not everyone succeeds, of course, but some do. One notable example is England's Queen Elizabeth II, who has served as an example of culturally valued virtues such as courage, patience, and courtesy, particularly during World War II and other crises.

Obviously, neither Martin Luther King nor Queen Elizabeth embody virtues that everyone values, and even those who value those virtues may not agree that these individuals embody them fully. However, these two examples help us think about a couple of the different ways that social conditions and histories enter into the construction and practice of personal virtues.

Some people overcome great personal and social obstacles to practice virtue and to help make their society better. Good examples of such people are members of minority groups, women, and others who suffer social exclusion and/or repression. Despite lacking access to the same resources as more powerful members of society and experience injustice and often physical and emotional abuse, they do not take the path of anger, bitterness, or virtue but rather astound both their enemies and their allies with their example of virtues such as patience, forgiveness, and generosity. Martin Luther King Jr. is an outstanding example of this kind of virtue.

Other virtuous people seem to become good not in spite of but because of their social conditions. Their personal histories, families, economic advantages, and cultural training all equip them to embody certain virtues. Not everyone succeeds, of course, but some do. One notable example is England's Queen Elizabeth II, who has served as an example of culturally valued virtues such as courage, patience, and courtesy, particularly during World War II and other crises.

Obviously, neither Martin Luther King nor Queen Elizabeth embody virtues that everyone values, and even those who value those virtues may not agree that these individuals embody them fully. However, these two examples help us think about a couple of the different ways that social conditions and histories enter into the construction and practice of personal virtues.

Monday, September 16, 2013

Bob's Bugatti and Singer's Ethics

Singer’s argument is simple but challenging: we are like Bob, the fictional rich guy who values his fancy car over the life of a child. We'd rather let innocent children die than give up our completely trivial luxuries.

How can Singer make this argument? His logic is that we spend money on non-necessary items instead of directing our resources ("throwing the switch") to ways to make life better -- even to make life possible -- for poor people, especially in developing countries. Singer believes that both individuals and governments should send aid to people in poor areas for famine relief and other urgent problems.

The most common to this argument might be that the little bit that one person can donate won't make much of a difference. This is not compelling to Singer, since he believes both that every individual has a moral obligation to donate whatever we can and also that the sum total of many small individual donations will add up to significant amounts. Further, he thinks we should pressure our government to devote more funds to foreign aid, especially for direct relief for victims of famine and other crises.

I think Singer's argument has a lot in its favor, especially because it pushes us to take responsibility for our inaction as well as our action. Most of the time we don't think we are choosing to let children die, but Singer challenges this assumption and pushes us to make our choices explicit. Passively standing by while people die (or other bad things happen) is as much a choice as more obvious actions are, according to Singer. We are not off the hook morally just because we caused a death through our inaction rather than our action. This is a lesson that can be applied in many areas, not just the problem of hunger in poor nations.

Singer's argument makes me think of a quote attributed to Dante Alighieri (but probably not really by him). It suggests that remaining "neutral" is in fact a moral choice, and one that deserves judgment just as more explicit choices do.

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Rules and ethics

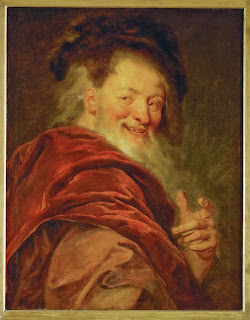

(Immanuel Kant)

From the perspective of deontological ethics, rules are indeed necessary because without rules, our moral ideas and behavior might be guided by subjective factors like self-interest, prejudice, loyalty, and the like. We would not be held to the same standard as others and would try to justify our actions with appeals to principles or foundations that are not really moral. Rights are a common kind of rule-based ethics. Rights are supposed to be possessed equally by all people in the relevant category (all citizens, all humans, all children, etc.) and cannot be violated.

Against this position, there are other philosophers who think that ethics does not require rules – and some who criticize rule-based ethics as a false or counter-productive approach to morality. Some of these point out that rules are always made by a particular person or group of people, and no person can escape his or her subjective perspectives, values, and interests. To imagine that we can come up with “objective” rules, in this view, is to kid ourselves. Sometimes, the rules just justify what we think is in our own best interest, or they try to give a “transcendent” and absolute quality to our subjective preferences or even just to something we hope is true but isn’t really.

Some people think that ethics can be a mixture of different kinds of approaches and values – maybe sometimes rules are necessary but they are not all that ethics requires, nor are they the only kind of ethic that matters. A good example of a mixed ethical model is just war theory, which includes some absolute rules (civilians can never be directly targeted) along with some conseequentialist calculations (you should not go to war unless you have a good chance of winning). I think that such mixing may be inevitable, or at least helpful, when we try to apply ethics to concrete situations.

Wednesday, September 4, 2013

The Great American Desert

At first glance, this doesn’t look like an ethics article, And no matter how many times you glance, or even look carefully, you won’t make a traditional ethical analysis out of Edward Abbey’s love letter to the desert. However, there’s a reason that Weston included this excerpt here – it makes us think about some of the different ways that values are developed, justified, felt, and expressed, as well as about the different objects or subjects that have value. Is the desert an object or a subject here? That is an interesting question – but here I will focus on the questions that Weston poses.

What values does Abbey describe here? Abbey describes both his own values and the values he thinks that the desert possesses. Both of these help explain why he loves and appreciates the desert and why he wants to protect it. At first he describes what is least lovable about the desert – the dangers and inconveniences, discomfort and emptiness. It turns out that this is also what he finds most lovable about the desert: its radical difference from most of what we value. It is unfamiliar, strange, not oriented or arranged for human comfort or even human survival. It is independent and above all wild.

Are these moral values? We could also ask if these are social ethics values – in other words, are they related to human society and collective life? Is ther emoral value in independent wild nature, including the parts of nature that do not really support human habitation? Abbey would say yes, I think. There is something profoundly moral – and not just emotional or aesthetic – in his love for the desert. By “moral” here I mean values that take us out of ourselves, that can guide us in a way that is not self-interested but rather oriented toward a more general interest.

Can love for nonhuman nature be moral? Why or why not? This is the question of whether nature can be a general value – and Abbey certainly thinks it can. For him, in fact, love of nature might be the most general value of all. The “silent world” of the desert, with its noxious bugs and extreme temperatures and toxic plants, shows us a world that does not exist for us and that takes us outside our personal and even human self-interest. As Abbey would say, “That’s why.”

What values does Abbey describe here? Abbey describes both his own values and the values he thinks that the desert possesses. Both of these help explain why he loves and appreciates the desert and why he wants to protect it. At first he describes what is least lovable about the desert – the dangers and inconveniences, discomfort and emptiness. It turns out that this is also what he finds most lovable about the desert: its radical difference from most of what we value. It is unfamiliar, strange, not oriented or arranged for human comfort or even human survival. It is independent and above all wild.

Are these moral values? We could also ask if these are social ethics values – in other words, are they related to human society and collective life? Is ther emoral value in independent wild nature, including the parts of nature that do not really support human habitation? Abbey would say yes, I think. There is something profoundly moral – and not just emotional or aesthetic – in his love for the desert. By “moral” here I mean values that take us out of ourselves, that can guide us in a way that is not self-interested but rather oriented toward a more general interest.

Can love for nonhuman nature be moral? Why or why not? This is the question of whether nature can be a general value – and Abbey certainly thinks it can. For him, in fact, love of nature might be the most general value of all. The “silent world” of the desert, with its noxious bugs and extreme temperatures and toxic plants, shows us a world that does not exist for us and that takes us outside our personal and even human self-interest. As Abbey would say, “That’s why.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)